Jump to different periods: Palaeolithic and Mesolithic (11000-4000 BCE) | Neolithic (4000- 2000 BCE) | Bronze Age (2,000 – 900 BCE) | Iron Age (900 BCE to CE 43) | Pictish (43 – 800 CE) | Viking / Norse / Scandinavian (800 -1472 CE) | Scottish and British rule (1472 CE- )

We have generally used the terms Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE). They cover the same periods as Anno Domini (AD) and Before Christ (BC).

Welcome

Burray and South Ronaldsay have played an important role in Orkney’s history and development. For example, Old St Mary’s Church, aka Lady Kirk in Burwick, marks where the first Christian missionaries are said to have landed. Thousands of years before that, people were buried nearby in the Tomb of the Eagles, and we also see the development of farming across the islands. The North Sea laps our eastern coastlines, the natural harbour of Scapa Flow lies to their west, and the Pentland Firth flows past the south of South Ronaldsay. As a result, this part of what we know as Orkney was a significant destination for traders, settlers and invaders. It became the home of industries linked to the sea and the land.

On this page, we provide an outline of what has happened on the islands over the last 13,000 years or so. To organise this, we use the terms Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE). They are equivalent to Anno Domini (AD) and Before Christ (BC).

The sections tend to grow in size as they get closer to the present. This is largely because we have a lot more evidence and material for later periods.

The Palaeolithic (14000-9000 BCE) and Mesolithic Periods (9000-4000 BCE)

For many years, it was thought that Orkney’s human history began around 6000 BCE, i.e. in the Mesolithic Period. However, there is growing evidence from archaeological research (such as that based at the Ness of Brodgar) that, in Orkney, human activity appears to have been present around 11,000 BCE, i.e. in the Palaeolithic Period. As the Ice Age was coming to an end, people arrived in Orkney. [There are various ways of setting the dates for these periods. Here we use the dating system the Ness of Brodgar project employs.]

Sea levels were up to 20 metres lower at the start of the Mesolithic Period. Consequently, the East of England was connected to what we now know as mainland Europe. Islands like Burray, South Ronaldsay and Hoy were part of the Orkney mainland. There was just one, reasonably narrow, entrance to Scapa Flow. An extended version of South Ronaldsay’s Hoxa Head was on one side, and a similarly expanded Flotta on the other. [Click to view a map of the entrance to Scapa Flow in 8000 BCE when Orkney was beginning to come out of the Ice Age]. The situation changed over the Mesolithic Period, so by around 6000 BCE, the shape of the islands had started to resemble what we see today.

The people who came to live here were largely nomadic hunter-gatherers, so there is limited physical evidence of their presence. Later, the shift to farming changed this.

The Neolithic Period (around 4000 BCE to 2000 BCE)

We know farming developed in many of the islands in the Neolithic period. The oldest preserved stone house in Orkney (and northern Europe) dates from around 3700 BCE and was part of a farmstead at the Knap of Howar on the island of Papa Westray. There is also evidence of the cultivation of crops and the raising of livestock on other islands. In Orkney’s west mainland, we find the most complete Neolithic village in Europe. Situated beside the Bay of Skaill at Skara Brae, it was in use from around 3180 BCE. Another cluster of buildings from the same time was found nearby. Close to the shore of Loch of Harray and known as the Barnhouse Settlement, it is not far from the Standing Stones of Stenness (as seen in the picture below). In South Ronaldsay, the Tomb of the Eagles came into use at around the same time.

The Bronze Age (2,000 BCE to 900 BCE)

Across Orkney, there is evidence that farmsteads flourished during the Bronze Age (2,000 BCE to 900 BCE). One result was that there appears to have been significant immigration around this time, particularly of women. (The ‘immigration’ that took place might have been similar to what occurred later in Viking times. Then, sexual slavery and large-scale movement of women were a common occurrence.]

Close to the Tomb of the Eagles, we find one of the best examples of a Bronze Age burnt mound or cooking/washing place in Orkney. There appear to be over 200 burnt mound sites on the islands.

The washing/cooking area was constructed with flat slabs (and sealed with clay). It is suggested that the water was probably heated by stones warmed by burning peat [click for more information].

The Iron Age (900 BCE to CE 43)

By the Iron Age, Orkney had developed a robust agricultural system that involved mixed farming, growing cereals like barley and wheat, and rearing sheep and cattle. Various tools have survived this period including bone combs used in weaving and quernstones for grinding grain. There are also examples of pottery ware. In terms of buildings, one of the most visible examples is brochs – round towers (broch is said to derive from ‘brough’ a Lowland Scots word used for forts). However, more recent work suggests they were often used for residential rather than defensive purposes.

Brochs started appearing around 300 BCE and the highest concentration of such buildings is in Orkney, Shetland and north Caithness. For this reason, the Vikings used the name Burray (or Broch Island) for South Ronaldsay’s northern neighbour. Four Burray brochs are currently listed on Canmore (and shown on the Open Street Map): Ayresdale Broch aka West Broch of Burray (in the grounds of Northfield Battery and Observation Post); East Broch of Burray (which is to the east of the Battery); The Hillock of Fea is a possible broch (but may be best described as a cairn): and Kyelittle which is listed as ‘severely denuded’ (just to the east of the Fourth Barrier and part of what was the blockyard for the construction of the barrier).

Two classic examples of brochs can be found in South Ronaldsay – one at the Cairns dig at Windwick Bay, another at Hoxa – the Howe of Hoxa. A second development was Weems – underground houses. ‘Weem’ is said to be derived from the Gaelic word ‘uamh’, meaning cave. However, just to add to the confusion, South Ronaldsay has Weems Castle, which looks to be the ruins of a broch (click for map). Unfortunately, not much is known about the culture and language of Orkney’s residents during this time.

The Pictish Period (43 CE – 800 CE)

A common way of discussing the next stage in Scottish history is describing it as the ‘Roman Period’. The Roman occupation of England and Wales had lasted from 43 CE to 411 CE. The Northern and Western Isles and much of the mainland escaped the Roman armies and Roman governance. Some Romans may have visited Orkney, for example, to trade, but not to occupy. Instead, it is more accurate to talk about the Pictish Period in Scotland and the activities of a group of tribes that largely spoke a Celtic language. This includes Gaelic [often derived from ancient Irish dialects], but it left few written records. The dates we use here (43 CE – 800 CE) are, thus, rough and ready. 800 CE may, or may not, be right for Orkney. 839 CE might be more accurate for the mainland. A major battle with Viking invaders took place around this time, resulting in the death of the Pictish king.

The first written mention of the Picts was by the Romans. It referred to their role in the Battle of Mons Graupius in c.80 CE. Their original name might have been something like Pecht (which can be translated to ‘the ancestor peoples’). However, in recent years, genetic studies have suggested that there wasn’t a single Celtic or Pictish group but various strands. It is now possible to talk about a genetic basis for regional identities. Picts were not the product of large-scale migration. In Orkney, for example, there appears to have been Pictish genetic continuity since the end of the Iron Age. This is interesting given the later invasion of the islands by the Vikings. Norse DNA is significant – it appears to have contributed to about 25% of Orcadian DNA – but Pictish and other earlier strands remain strong.

The scale and scope of Pictish involvement in the life of Burray and South Ronaldsay is unclear. There is evidence of their presence, e.g. at the Brough of Bursay, and in the East Broach of Burray. We also know the islands had been incorporated into the Pictish kingdom by around 565 CE. Orkney was certainly viewed as “Picti”. However, from the evidence of various activities from this period, e.g. the remains of a large feast at The Cairns in South Ronaldsay, they are not always the outcome of Pictish activity.

Archaeological research generally indicates that the Picts were largely farmers. They often lived in villages. However, we also know that some were hunters, and that others were seafarers and warriors. From the number of symbol stones discovered over the years, we also know they were skilled in crafts. Indeed, Pictish stones have become one of the lasting and distinctive features of the period.

Some 350 Pictish stones carved with symbols and/or designs are listed in Scotland. Orkney has been home to eight accomplished Pictish symbol-bearing stones, four small stones with rough versions of symbols, sixteen or seventeen cross-slabs of different kinds and two pieces of church furniture. Unfortunately, in Orkney, Shetland and Caithness, no stone with symbols has survived upright in the landscape. Some have been found at the likely place of origin. St Peter’s Church, South Ronaldsay, had a fascinating symbol stone carved on both sides (possibly because it was reused). It was then reused, again, to form part of an east-facing window in the church and subsequently removed to the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland in Edinburgh. The one carved, and probably Pictish stone, left on the island is in Old St Mary’s, Burwick. Known as the Ladykirk Stone, it is a rounded grey whin stone carved with two footprints. It is said to be a Pictish coronation stone. What we do not know is the meaning of many of the symbols that have been discovered.

Another feature of some discussions or representations of Pictish life is the idea that they had marks on their skins (stigmata) and/or were ‘painted people’, i.e. they were tattooed. One possible explanation is that, over the years, there may have been some confusion regarding the origin of the word ‘Pict’. Rather than deriving from ‘Pecht’, some believed it could flow via the Romans from the Latin word pingere ‘to paint’; or the Greek word pictus – ‘painted’. However, as Stuart McHardy has commented, it now seems ‘highly unlikely that the Romans gave them their name. In other words, ‘the idea of the term meaning ‘the painted ones’ has no basis in fact’ [A New History of the Picts, 2011]

The written material from this period is overwhelmingly from non-Picts who may have wanted to put their spin on what they report. What we have is mostly not original but ‘copies of copies’. Sally M Foster has pointed out that:

Only one text of any kind can fairly be claimed as Pictish, the so-called king list, which give lengths of reigns. Two versions exist, neither of which are in a manuscript older than the 14th century and one of which is heavily gaelicised. [Picts, Gaels and Scots, 2014]

It was also during this period that Christianity reached the highlands and islands. From around the 8th century, we find the appearance of cross-slabs across northern Scotland. Some of these had both traditional Pictish symbols with Christian ones.

The arrival of Christianity

When the Roman armies withdrew from England and Wales, Germanic tribes raided and took over. One element of this was the elimination of much Christian thinking and activity amongst their population. Significantly, Ireland had not been invaded by the Romans (or the Germanic tribes) in the same way. Christianity had been growing, and so had the Gaelic language and culture.

The latter had also crossed the sea to what we now know as Argyll (meaning ‘coast of the Gaels) and later Skye. A kingdom had been established that included part of County Antrim in Ireland and much of Argyll across the water in what we now know as Scotland. [Scotland derives from Scoti, the Latin name for the Gaels. Scotia was the land of the Gaels.] By the late Middle Ages, Scotland and Scots were used in much the same way as they are today.]

This had begun in the fifth century, but the significant moment in relation to Christianity had happened in 563 CE. In that year, Columba (or Colmcille – “Church Dove”) had sailed with 12 others to the eastern part of Dál Riata. This may have been at the invitation of his kinsman Conall mac Comgail, King of Dál Riata. One result of this visit is said to be that the King gifted him the Island of Iona as a base for his work.

The Iona group, led by Columba and his successors, went on to nurture change. They brought Christianity, monasteries and literature to the north of Scotland. Alongside this, accounts of their activities appeared. Most notably, Adomnán’s Life of Columba, (written between 697 and 700 CE) was especially influential (Adomnán was the ninth Abbott of Iona from around 679–704). We discover, for example, what is said to be the first sighting, in 565 CE, of the Loch Ness Monster. Columba was on his way by water, via The Great Glen and Loch Ness, to Inverness. He was going there to meet King Bridei (or Brude), King of Fortriu. This was ‘Pictland’ and was a risky enterprise. However, while Bridei was not known to be Christian at this time, it is said that he respected Columba, and it is possible that he converted to Christianity.

The coast at Burwick is where the earliest missionaries are thought to have landed in Orkney. Adomnán’s Life of Columba indicates that Cormac Ua Liatháin arrived around 580 AD in South Ronaldsay on his second major voyage from Iona (probably ). However, he may have stopped first in Pictish Caithness. There is some evidence of Irish priests (Papar) being based here around this time. [The North Coast Visitor Centre in Thurso has various artefacts and two interesting Pictish stones.]

This is how Adomnán describes how Cormac was recommended by Columba to King Bridei (Brude), ‘in the presence of the ruler of the Orcades (Orkneys)’:

Some of our brethren have lately set sail, and are anxious to discover a desert in the path less sea ; should they happen, after many wanderings, to come to the Orcadian islands, do thou carefully instruct this chief, whose hostages are in thy hand, that no evil befall them within his dominions.

Adomnán comments that Columba took care to give this direction because he knew that after a few months, Cormac would arrive at the Orcades. [The Life of St Columba, Book II. 71]. Some commentators suggest that Columba himself visited Orkney, but there is little or no evidence to support this. Similarly, there has been some suggestion that Saint Ninian came to Orkney before Cormac (see Picken 1972). However, there is no contemporary evidence to support that.

The Viking / Norse / Scandinavian Period (800 CE-1472 CE)

While Viking and Norse are often used interchangeably, there is an underlying difference. The term ‘Viking’ is from ‘Old Norse’ and was used, generally, to describe pirates and the raids launched from various territories in what we now describe as Scandinavia. However, it was also used to discuss those sailing longboats to other areas to explore, trade and settle. The various territories were later consolidated into the kingdoms of Norway, Sweden and Denmark. ‘Norse’ refers here both to a North Germanic language (Old Norse), and to people living and working in, or with origins in, Norway, Sweden and Denmark. ‘Old Norse’ was in widespread use from about the 9th to the 13th centuries. In short, Vikings tend to be viewed as raiders who might settle, Norse people as settlers.

The Danes broadly sailed to, and took over, a swathe of what we now know as the north and east of England in the late 9th Century. Later known as the Danelaw, this area, stretching from London to York and across to Lancashire, had to abide by Danish Law. Northumbria was raided but not occupied in this way. Swedish raiders hit the more northerly areas like Jórvík (now York) and, along with the Norwegians, parts of Scotland and the Northern Isles. So it was that from around 800 CE to 1468/72 CE, significant areas of what we now know as Scotland were colonised by Norwegians [and were helped in this by other Scandinavians]. ‘Scandinavian Scotland’ included Iona (first raided in 794 CE, and abandoned by the religious community based there some fifty years later). Later, the Hebrides effectively came under the control of the King of Norway and, as a result, dominated the trade route down to Dublin and Ireland.

In addition to what we now know as Britain, Viking activity took place across a wide area. This included the Baltic coast, and various trade routes across Eastern Europe, Greenland, Iceland and Normandy. It appears that they even managed to reach the North American coast. In short, they became a major force.

The Viking impact on Orkney was far-reaching. Initially, they looked to have engaged in ‘hit and run’ raids. The aim was to obtain valuable goods and resources that could be traded or employed elsewhere. This included both the taking of slaves and extortion (taking payment from local landowners, etc., to avoid being attacked). They then turned to occupation. Defeated Viking warriors from kingdoms opposed to joining a united Norway appear to have taken refuge in Orkney. The King of Norway decided to act – and annexed Shetland and Orkney in 875 CE.

Some key consequences

The activities of Viking raiders, Norse settlement, and incorporation into the newly created kingdom of Norway had several fundamental consequences for Orkney.

First, both Orkney and Shetland were part of Norway (and then Denmark) for longer than they have been part of Great Britain. Linked to other elements, such as its Pictish/Scots/Gaelic inheritances and the simple fact that much of Orkney is closer to both the Arctic Circle and Norway than it is to London, there remain significant implications for island identity. Many people view themselves as Orcadians first, Scots second. When flags are raised, it is rare to see a Union Jack. Those not living on the mainland will often, and understandably, place their island before any mention of Orkney.

Second, the dominant language in Orkney became – and remained for around a thousand years – a variant of Norse. This was – Norroena or Norn in Scots (click for more information). Many of the key placenames reflect this. For example, South Ronaldsay and North Ronaldsay are named after St Ronald, a former Norwegian Earl of the Orkney and Shetland Islands appointed by King Sigurd I in 1129. The name is derived from Old Norse – Rǫgnvaldsey, meaning ‘Ronald’s island’. One of his lasting contributions was the building of the Cathedral of St. Magnus in Kirkwall (Christianity had become a significant presence in Norwegian life). There is an interesting contrast between Orkney and Shetland in relation to language. As the Scots Language Centre notes: ‘Orkney dialect differs from Shetland in that Shetland follows Nordic stress patterns whereas Orkney has a rising intonation akin to Welsh or Irish’. In other words, and perhaps not surprisingly, the Pictish influence, while reduced, was still present in Orkney, and dialects may also have been influenced by trade with Ireland and the Hebrides and beyond.

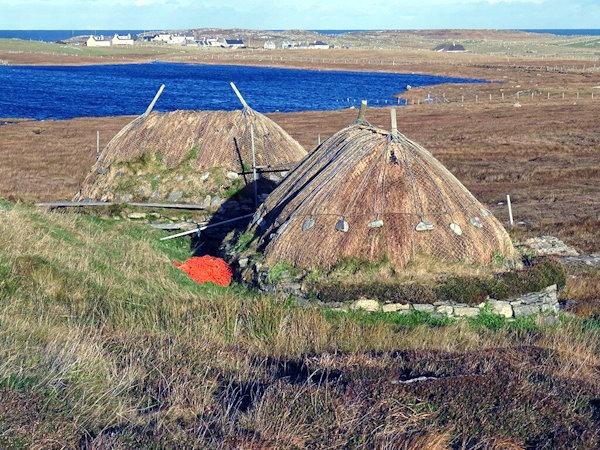

Third, while farming remained central to island life throughout this period and well beyond it, the Norwegian settlers made some key changes. This included introducing new livestock breeds, improving farming methods, and innovation in areas like milling. The best-known example of the last is at Shawbost in the Isle of Lewis. Sadly, there are no examples in Orkney from the same period, but the Click Mill, built in the 1820s, close to Dounby, shares some elements with the horizontal water mills used by Norse farmers.

Fourth, the spoils of Viking raids did not necessarily leave the islands. Indeed, the second-largest Viking hoard discovered in Scotland came from Burray. It was found in 1889 by a local man whilst peat-cutting in what was known as North Town Moss. (Click for details of the hoard).

Fifth, the arrival of the Vikings and Norse inhabitants appears initially to have led to a significant decline in Christian worship. Later, with the development of Christian worship in Norway and Denmark, we find a revival in Orkney during the 11th or 12th centuries [see the History of Catholicism in Orkney].

Three events involving South Ronaldsay

The first event links back to Rögnvald. Rögnvald’s son (by a slave) Torf-Einarr established a dynasty that dominated Orkney for many years – but was not without significant conflict. His son, Thorfinn Torf-Einarsson, aka Thorfinn Skull-splitter, turns up in the Orkneyinga saga. He died around 963 and was buried, it is said, at the broch at the Howe of Hoxa in South Ronaldsay.

A second important event concerns Margaret, Maid of Norway. She died in 1290 (aged 7) either in what is now known as St Margaret’s Hope or just round the coast in, or beside, Widewall Bay. Locally (and by some historians), it is said that the village is named after her. Margaret, Maid of Norway, was the granddaughter of King Alexander III of Scotland, who died in 1286, leaving Margaret as his sole heir. Her father was King Eric of Norway. Margaret was on her way to mainland Scotland (Leith) from Bergen. Whether the result of bad weather or another concern, such as Margaret’s illness, the boat entered the Pentland Firth and landed at what we now know as St Margaret’s Hope. There is some suggestion that Margaret was suffering from food poisoning or a form of seasickness. She appears to have died within 3-5 days of landing. Her body was taken back to Bergen for burial. There were 13 rivals for succession, and the situation became rather dire.

Some historians and the Catholic Church add a third event. They argue that the village’s name refers to Margaret of Wessex (1045-1093). She, too, had been a passenger in a boat that had met the turbulent waters to the south of the village and had, apparently, landed in the Hope or by Widewall Bay. The story goes that she prayed for the storm’s end and for divine guidance. She was granted calm waters, a safe trip to Scotland, and marriage to King Malcolm III. Canonised in 1250, she became St Margaret of Scotland. The glass panel above is from St Margaret’s Chapel in Edinburgh Castle (which was founded by her son, King David I). Some also point to another Margaret – St Margaret of Antioch (or Margaret the Virgin). Given that Orkney was under Norse control at this time, and that Norse was the dominant language, it seems a little unlikely that either of these Margarets is the source of the Hope’s name.

The end of Nordic rule

As Caroline Wickham Jones (2013) has pointed out, from the late twelfth century, Orkney increasingly came under Scottish political influence. In part, this was because the Earls of Orkney often had Scottish lands in places like Caithness. They were also ‘members of the Scottish aristocracy and related to other Scottish nobles by both birth and marriage’ and looked to both the Norwegian court in Bergen and the Scottish court to the south (Wickham Jones 2013: 179). Margaret, Maid of Norway (discussed above), was a classic example of the connection between the Norwegian and Scottish courts.

A further example of Scottish influence in Orkney was that of Henry Sinclair of Roslin near Edinburgh, who became the Earl of Orkney in 1379. While allied to the Norwegian crown, he had strong connections to the Scottish court. He spent a considerable amount of time in the islands. He looked to develop Orkney and was responsible for building a defensive castle close to the Cathedral in Kirkwall (which no longer exists). After he died in 1400, the Sinclair family remained in control in Orkney, but the next two Earls do not appear to have spent time in the islands. David Menzies, a Scot, was appointed by the first of them (another Earl Henry II) to oversee Orkney and be his son’s Guardian. He appears to have treated Orcadians very poorly. This included levying illegal fines, seizing goods and cargoes, and arresting those who spoke out against his activities. In 1425, a formal Complaint was made that set out local people’s grievances. One complaint, from South Ronaldsay, concerned Menzies ‘depraved indifference to attacks by certain ‘Wild-Scots’ (Willeschotta) on the island’ (Groshe 2021). It looks to have been the last such complaint in Orkney made in Norn (the Norwegian language). There had been a growing movement towards the use of the Scots language by senior officials in the church, previous earls, and those who worked for them, as well as in trade beyond Orkney. This said, Norn remained in use, particularly in rural areas of Orkney, up to the late eighteenth century (Wickham-Jones 2013: 151).

Then something fundamental happened. Orkney effectively became a Scottish Earldom. This arose from a marriage agreement between the daughter of King Christian I of Norway and Denmark and James III of Scotland. A royal dowry of 50,000 florins was promised, but did not appear. King Christian I didn’t have the money, so Orkney was effectively pledged to Scotland in 1468.

Three years later, James III gained the earldom of Orkney and, by an act of Parliament, passed on 20 February 1472, the whole of Orkney was said to be the property of the Scottish Crown.

Scottish and British rule (1472 CE- )

One of the striking features of this era is that, compared to its forerunner, the ‘Viking / Norse / Scandinavian Period’, relatively little attention has been given to Orkney, Shetland, and other islands by mainstream writers. Yet it was a time (particularly from 1540 to 1814) when there was, as Peter Marshall puts it, ‘a sequence of dramatic – and often traumatic – processes, which profoundly reshaped patterns of society and redirected the course of countless individual lives’ (2024: 3). As he goes on to show, islands like Orkney were ‘revelatory places’ in this respect. They raised important questions around the nature of nationality and identity, and are paradoxical places:

As communities, they are prescribed by the clearest. most non-negotiable of boundaries. But they can also so be surpisingly open and permeable, the encircling sea as much a conduit as a barrier. In relation to mainlands, they are by definition marginal, if not isolated and secluded. Yet by virture of participation in trade and proximity to sea-lanes, islanders often enjoy greater contact with the outside world than inhabitants of inland regions. (Marshall 2024: 5-6)

Over time, the power of the Sinclairs waned, in part, because of conflicts between different factions within the family. In 1529, this resulted in the Battle of Summerdale/Summers Dale between the Orcadian Sinclairs and the Caithness Sinclairs (click for map). It is said to be the last battle on the Orkney mainland. The Orcadians won and appear to have killed nearly all their opponents (500 men).

Troubled times

Summerdale didn’t end the problems faced by the Orcadian Sinclairs. New aristocratic families had appeared, and in the process, one particular family – the Stewarts – came to the fore. Robert Stewart (1533-1593), the illegitimate son of James V of Scotland and a half-brother of Mary Queen of Scots, became the 1st Earl of Orkney. Along with his son Patrick, he is remembered ‘for the hardship and cruelty of their times, and this period was to herald an all-time low for the people of Orkney’ (Wickham-Jones 2013: 153). If Robert Stewart was bad, his son Patrick was even worse. He was known as ‘Black Patie’, and ‘became a symbol of coercion, cruelty and tyranny’ (Marshall 2024: 154). ‘Black Patie’ was executed in 1615. His father, Robert Stewart, had been hanged a short time before him.

In 1603, the situation began to change. On the death of Queen Elizabeth I, James VI of Scotland became James I of England. This had fundamental repercussions (see Jackson 2025). In March 1611, a decree was issued stating that it was the will of the king that his subjects should ‘live and be governed under the laws and statutes of this realm only, and by no laws of foreign countries’ (op. cit.: 165). This went beyond the 1472 Act by excluding external laws and including England. Orkney and Shetland had formally become part of Britain, and Norse law had been set aside.

While these were radical changes, they probably didn’t have a major impact on the lives of ‘ordinary people’. As Rosemary Hebden (2008: 26) put it, they were no better off under the system that followed the end of Earldom, and probably did not notice any change. However, in the case of Burray, some significant alterations to local life resulted from the actions of some members of the Stewart family.

From 1550 to 1768, Burray was in the hands of the family (Struthers 2013: 15-27). The Bu estate was the centre of much activity. There was a house here from Norse times, and perhaps even earlier, but William Stewart of Mains and Burray (circa 1575-1661) looks to have rebuilt it in the 1640s. Struthers draws our attention to his coat of arms (dated 1649) on the north wall of the old bothy, and a marriage stone concerning his marriage to Barbara Stewart in 1638 can be found above the washhouse. The Bu is now a listed building (click for details), as is another product of William Stewart’s activities in the village – the Storehouse (Store-House), Westshore. Its purpose was to store the grain produced and needed by his tenants. Another significant contribution is said to be William’s funding of the renovation of the local Burray church, St Lawrence’s, which was completed in 1621. There is at least one family grave in the churchyard.

Orkney did not escape the ‘Little Ice Age’ that much of Europe experienced. This had a particularly negative effect on agriculture. It appears that the early 1630s were particularly challenging. The bishops of Orkney and Caithness petitioned the Privy Council concerning the impact of ‘tempestuous and bitter weather’, the destruction of the harvest before it could be taken in, and reported that some were so desperate that they had run into the sea and drowned themselves. Caroline Wickham-Jones summed up the situation as follows:

There was a general climatic deterioration, and this, coupled with the previous impoverishment, meant that rents and taxes became harsher and harsher. Many farmers had to give up, and poverty was rife. Famines became common, and even the landowners went bankrupt. Life for the average Orcadian was to take a while to improve, and the seventeenth century was one of poverty and agricultural exhaustion for most people. (2013: 155)

Additionally, the plague arrived from Scandinavia in 1624. It, in turn, led to the halting of trade to these areas.

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms

On top of all this, Orkney suffered badly from the effects of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms between 1639 and 1653 (the kingdoms being England, Scotland, and Ireland that were part of a ‘personal union’ under Charles I). Included were the Bishops’ Wars (1639-1640), the First and Second English Civil Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland and the Anglo-Scottish War of 1650–1652. A significant number of Orcadians were forced to join a Royalist army headed by James Graham (the Marquis of Montrose and the king’s Lord Lieutenant in Scotland). They had little training and were augmented by a small corps of German and Danish mercenaries. Early in April 1650, around 1000 men set sail from Holm in mainland Orkney for John O’Groats. From there, they marched for two weeks to the southern end of Sutherland. In the process, they failed to gain further support from the local clans.

On Saturday, April 27, 1650, the ‘Orcadian’ soldiers met part of Cromwell’s New Model Army in Carbisdale (close to the Kyle of Sutherland). In a quick battle, 400 islanders died (200 of whom drowned trying to escape across the Kyle Estuary). Another 450 were captured, many of whom were later consigned to work in lead mines. A small number (around 40) were released to return home as they had been conscripted and had children. It appears that around 100 soldiers had been able to escape the battlefield (including the Marquis of Montrose). However, the Marquis (James Graham) was captured within a few days and executed. [For an account of the battle and its aftermath, see Chapter 6 in Peter Marshall’s excellent book. Click for an overview of the battle, and its outcomes, from The Orkney News, April 27, 2025.]

Back in Orkney, a meeting of lairds (who were largely Royalists) refused to support the governor of Kirkwall and his officers. In addition, ‘commoners’ were said to be in a ‘revolutionary ferment’. As a result, the ‘government in Edinburgh, and the sheriff in Kirkwall, lost control of the islands’ (Marshall 2025: 278). Led by a man known as Currey (we have no evidence of his first name), a force of 600 commoners was able to take control of Kirkwall and ‘expel or imprison lairds attempting to debate public business’ (op. cit.). However, by April 1651, the lairds had fallen in line with Scottish government demands and agreed to support raising a new regiment. Currey and other rebel leaders were arrested. A Cromwellian garrison was established in Kirkwall early in 1652. However, as one of Cromwell’s soldiers noted, conditions remained poor for many local people: ‘Their schooles of learning are in every house, and their first lesson is to hunt the louse’ (op cit).

Devilry and witchcraft – and other problems

One further dimension has been highlighted by Marshall (2025: 182-238) – devilry and witchcraft. Between 1594 and 1708, there were at least 97 people indicted as witches in Orkney. This was more than double the number per head in Scotland as a whole. Furthermore, the vast majority were women (81). The trials appear to be clustered – often linked to times of turmoil. Ragnhild Ljosland and Helen Woodsford-Dean have argued that there is a connection with political upheaval and famine. They also suggest that a ‘cluster of witch trials coincided with James VI’s siege of Kirkwall and Earl Patrick’s downfall in 1615, but without any evidence of a direct link other than the general unrest in the period’. In addition, they report that a lot appears to depend on the people involved: ‘One keen witch-hunter in a position of power can make a big impact’. In South Ronaldsay, there were several cases. For example, Jonet of Cara was burnt in Ronaldsvoe (Marshall 2024: 185), John Budge was named as a probable victim (op. cit.: 214), and Edward Richardson, the minister at Old St Mary’s Church, aka Lady Kirk, had to order the opening of graves in front of certain local people said to be wicked and to have caused their deaths. It was claimed that the ghosts of several drowned fishermen were haunting the area. No accusatory signs appeared, and Richardson declared the matter closed.

In the final years of the 17th century, the cost of renting land continued to increase. The middlemen between the owners and tenants (known in the Highlands as tackmen) put up the price of land. This had the effect of driving some tenants out of Orkney and of adding to the number of people experiencing severe poverty. Additionally, a poll tax was levied between 1693 and 1695 to help fund the Nine Years’ War, which was being fought against the French on the continent. As Rosemary Hebden has commented, ‘it applied to everyone except young children and those who lived “on charity”‘ and was levied in addition to various other taxes (2011: 29-30). Things were made worse in 1696 by one of the worst harvests experienced in Orkney. The result was that land fell out of use, and there was a great deal of suffering. On top of this, French boats appear to have raided Orkney at this time.

Things can only get better – Orkney in the 1700s: crofting and kelp production

Farming was slow to recover, and some new crops, such as potatoes, were introduced, in this case, in 1750. Another innovation was the use of seaweed to fertilise crops. There was also a growth in flax production that was originally established by Norwegian settlers. However, perhaps the most significant change in farming in the early eighteenth century was the removal of tacksmen and run-rigs (strips of land that moved between tenants so that the best land was shared). They were replaced by crofting. This entailed individual tenancies, and rents were being paid directly to the landowner. However, there were at this time, ‘no tenants’ rights, and the size of a croft was deliberately too small to allow self-sufficiency’ (Wikipedia). Today, a croft is basically ‘a small piece of agricultural land, a sort of micro-farm, which may, or may not, have a house on it’ (Historic Environment Scotland). Often grouped into ‘townships’, each crofter has their own patch, and can also access common lands for grazing livestock or for communal activities (op. cit.).

One of the factors that powered the move to crofting was the need to house the growing workforce involved in processing seaweed into kelp. Kelp production became a key element of the Orcadian economy. This is how Jane Lindsey put it:

Seaweed, when burned into ash, provided the alkali for making soap and glass – especially valued for the fine window glass that had become popular in the mid C18th. It could also be further processed elsewhere to extract iodine and silver iodide. By the early C19th 60,000 people were working in kelp manufacture in Scotland and £70,000 profit was being made in the Hebrides alone. At its peak crofters on Orkney were producing 3000 tonnes of kelp ash a year – it was worth £22 a tonne. The crofters were paid £2 a tonne. (Snapdragon Life)

Kelp-making is said to have begun in Orkney in 1721 through the efforts of James Fee of Whitehall in Stronsay. The kelp boom, which followed, reached its peak between 1770 and 1830. Production was spread across the islands, but there were particular centres such as Sanday, Stronsay and Westray. [If visiting Stronsay, check out the Heritage Trail]. This said, both Burray and South Ronaldsay were still producing around 125 tons in the 1790s (compared to a total of around 1100 tons in the three islands above). The industry is said to have employed close to 3000 people across Orkney at its peak, and had major implications for shipping. However, it wasn’t without its opponents. Melting the kelp affected people’s eyesight and could lead to blindness (op. cit.). It was also blamed for the extreme famines resulting from crop failure and dying animals between 1739 and 1742. This led to a major riot in Stronsay in May 1742, which, in turn, spread to other areas and islands. [Click to read a piece by Bill Miller on Orkney’s Kelp Riots]. With kelp prices dropping radically after 1830, the activity was no longer profitable. The result was significant job losses and local depopulation.

Whaling, fishing and the Hudson Bay Company – the rise of Stromness

The sea had created other opportunities for work. Stromness became a key port for provisioning and recruiting crews for the Arctic whaling industry from around 1770 to 1870 (Arctic whaling looks to have begun around 40 years earlier). It was, for many years, a highly profitable but dangerous industry. Lobster fishing was also a significant feature of Scapa Flow. As Majorie Hebden reports, by 1775 live lobsters were being shipped to London (2011: 31). Deep-sea cod fishing and herring fishing were also growing from the 1750s. Other industries, such as straw plait manufacture and the manufacture of linen and woollen cloth, were in decline. The latter had ‘wholly ceased’ with the rise of new technologies some years later (Learmouth 1841). Stromness had grown both in size and economic significance, and much to the disgust of businesses in Kirkwall, they were the focus of attention.

A further important development was the establishment of the Hudson Bay Company. Charles II granted a charter in 1670 to create the company, which aimed to map a northwest passage to what is now known as Canada and to develop the largely unexplored area near Hudson Bay. The Orkney mainland was an obvious choice, as it offered a direct and shorter route than almost anywhere else in what is now known as Britain, and had been used before in Norse times.

Stromness became the centre for the company’s activities in Orkney, receiving various goods from England and then dispatching them to Hudson Bay. The population of Stromness continued to increase, rising to 2199 people in the 1794 census. Crucially, Orkney also became the main source of labour for developing production in Canada. It grew to over 500 employees (mostly men) by the end of the eighteenth century, 80% of the total workforce. The company’s initial focus was the highly profitable trade in beaver fur, which it came to dominate. Over the years, it developed a range of additional activities.

The Hudson Bay Company required a range of jobs to be filled. These included guards, trappers, labourers, washerwomen and specialist posts such as doctors. John Rae (1813-3), the Orcadian who became famous as an explorer, was a qualified surgeon and worked for the company in the Bay area for around ten years. His father had also been the Hudson Bay Company’s chief representative in Orkney with a particular responsibility for hiring workers. The family home (the Hall of Clestrain in Orphir, a grade A listed building dating back to 1769) was across the bay from Stromness. Previously, the land had been owned by the Sinclair family.

Another important local figure involved with the Hudson Bay Company was William Tomison (1739-1829) from South Ronaldsay. At the age of 20 (in 1760), he signed on with the Hudson’s Bay Company as a labourer based in Canada. Over the years, he worked his way up the Company and became the inland chief. He retired in 1803 but soon wearied of the experience, returning in 1806 to take up junior roles. In 1810, he finally returned to South Ronaldsay. Having no direct heir, he bequeathed a large part of his accumulated wealth to establish a free school for local children (for more details see Tomison’s Academy – a Category B listed building).

Social and political change

There was significant social and political change, particularly following the Battle of Culloden in 1745, when many big estates were taken over from Jacobite landowners by the government.

Developments in agriculture, industry

The revolution in farming, industry, learning and communication – Orkney in the 1800s

World Wars, oil and alternative energy – Orkney in the 1900s

[We are in the process of preparing these final sections]

Further reading

Adomnán (1874). Life of Columba. (Edited by William Reeves). Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. Download from the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/lifeofsaintcolum00adamuoft

Edmonds, Mark. (2019). Orcadia. Land, sea and stone in Neolithic Orkney. London: Head of Zeus.

Foster, Sally M. (2014). Picts, Gaels and Scots. Early Scotland. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

Gerard, Rev. John (1855). United Parishes of South Ronaldsay and Burray. Statistical Accounts of Scotland – NSA Vol XV. https://stataccscot.ed.ac.uk/static/statacc/dist/viewer/nsa-vol15-Parish_record_for_Ronaldshay_and_Burray_in_the_county_of_Orkney_in_volume_15_of_account_2/

Grohse, Ian Peter (2021). ‘Late Medieval Vikings. The MacDonald raids on Orkney c1461’, https://www.ssns.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/10_Grohse_InnerSeas_2017_pp_274-290.pdf .

Hebden, Rosemary. (2008). Eday. Orkney’s best-kept secret. Eday: Carrick Press. [The first chapter provides a concise overview of the history of Orkney.]

Jackson, Clare. (2025). The Mirror of Great Britain: A Life of James VI & I. London: Allen Lane.

Learmonth, The Revd Peter. (1841). Parish of Stromness. The Statistical Accounts of Scotland 1791-1845. https://stataccscot.ed.ac.uk/data/pdfs/account2/StAS.2.15.26.P.Orkney.Stromness.pdf

Lindsey, Jane. (2021). The history of Scotland’s kelp industry, Snapdragon Life. [https://www.snapdragonlife.com/news/blog/the-history-of-scotlands-kelp-industry/].

Ljosland, Ragnhild and Woodsford-Dean, Helen. (undated). Witchcraft Trials in Orkney. Orkney Heritage Society (https://orkneyheritagesociety.org.uk/projects/orkney-witchcraft-trial-memorial/history-of-witchcraft-trials-in-orkney/)

McHardy, Stuart. (2011). A New History of the Picts. Edinburgh: Luath Press Limited.

Marshall, Peter. (2024). Storm’s Edge. Life, death and magic in the Islands of Orkney. London: William Collins.

Miller, Bill. (2025). Stronsay’s Kelp Riots, The Orkney News. [https://theorkneynews.scot/2025/11/01/stronsays-kelp-riots/].

Nicks, J. (2003). William Tomison in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6. University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003. https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tomison_william_6E.html.

Peace’s Orkney and Shetland Almanac and County Directory (1874). Kirkwall: William Peace. https://archive.org/details/peacesorkneyalma1874peac/page/n7/mode/2up

Picken, S. D. B. (1972). The Soul of an Orkney Parish. Kirkwall: The Kirkwall Press. https://archive.org/details/souloforkneypari0000stua.

Struthers, J. M. (2013). Broch Island. A history of the island of Burray in Orkney. Published by J. M. Struthers via lulu.com.

Stewart, Ian. (2025). The Celts. A modern history. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Sutherland, Ewan. (2020). Captain James Sutherland of Duffus (February 9, 2020). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3534959 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3534959.

Watson, The Revd Mr. James. (1795). United Parishes of South Ronaldsay and Burray. Statistical Accounts of Scotland – OSA Vol XV: https://stataccscot.ed.ac.uk/static/statacc/dist/viewer/osa-vol15-Parish_record_for_Ronaldshay_and_Burray_in_the_county_of_Orkney_in_volume_15_of_account_1/

Wickham-Jones, Caroline. (2013). Orkney. A historical guide. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

___

The opening photograph is of St Margaret’s Hope in January. The building on the left is the bothy at Smiddy Banks | mks – CC BY-NC-SA licence.

If you find any mistakes in this piece or believe something needs to be added, please let us know.

Referencing this page: Smith, M. K. (2026). A (very) brief history of South Ronaldsay, Exploring South Ronaldsay. St Margaret’s Hope. [https://exploringsouthronaldsay.net/a-very-brief-history-of-south-ronaldsay/. Accessed: insert date]

updated: January 20, 2026